Dear All, because of the current situation activities of our network are suspended. Thank you for your understanding. Best regards, Federico Gobbo

Author: Federico Gobbo

Meertaligheid in het Amsterdamse onderwijs: Van voorschool tot universiteit

Deze zomer wordt het Europese project Mobility and Inclusion in a Multilingual Europe (MIME) afgerond. Een consortium van 22 wetenschappelijke teams afkomstig uit 16 lidstaten van de EU heeft dit programma-onderzoek uitgevoerd, met financiering van het Zevende kaderprogramma voor onderzoek (KP7) van de Europese Unie. De resultaten worden gepresenteerd in een Vademecum, dat op 27 juni feestelijk wordt gepresenteerd in Amsterdam.

Het Vademecum wordt op 19 juni officieel aangeboden aan de Europese Commissie in Brussel. Bij de presentatie op 27 juni worden de bijdragen van de twee teams van de UvA – van het Amsterdam School for Regional, Transnational and European Studies (ARTES) en het Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research (AISSR) – uitgelicht.

Vragen? Download PDF

Contested Languages in the Old World conference to be held in Amsterdam

In May 2018 we will host the third edition of the CLOW series conferences, devoted to contestedness in European languages. Please check the official web site for more information.

Public debate on multilingualism in education

The detail program of the conference on the Politics of Multilingualism is on line

For all people interested, the program of the conference on the Politics of Multilingualism is now available on line.

International Colloquium on “Language Skills for Economic and Social Inclusion”

FYI

International Colloquium on “Language Skills for Economic and Social Inclusion”

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany

12-13 October 2017

https://www.projekte.hu-berlin.de/en/okonomie-und-sprache/conferences/upcoming?set_language=en

General goals

This conference aims at exploring the relationship between individual language skills and people’s integration in the economy and in society in general with a special focus on the labour market. Language skills can be viewed as human capital having a positive influence on people’s income, employability and social inclusion. This holds for immigrants, refugees and mobile people who can benefit from the knowledge of the official language(s) of the host country, but also for citizens learning foreign languages and using them in the workplace.

Background

Learning foreign or second languages has for a long time been associated with openness to other cultures. In recent decades, nevertheless, the discourse on language learning has gradually changed. Language skills are viewed as part of individuals’ human capital that can contribute to their economic welfare, increase productivity and foster growth. At the same time, language learning can promote social inclusion. As a result of recent massive migration flows to Europe both the Council of Europe and the EU have emphasised the importance of language skills for the economic and social integration of migrants and refugees.

There are some sound economic reasons behind these claims. Being a particular form of human capital, language skills may have a positive effect of the economic and social inclusion of individuals in different ways. Language skills in the official language of the host country may have a positive impact on immigrants’ income, measured in terms of earning differentials; foreign language skills may be associated with a higher employability, and with a lower probability of being dismissed when the costs of the workforce increase. Language skills, therefore, may facilitate the participation and the inclusion in the labour market, higher earnings and the possibilities of finding a job or holding it. Language skills can also promote a better inclusion in society. Employment, in fact, is one central aspect of inclusion.

Languages are necessary (although not sufficient) for social inclusion and cohesion. The Social Policy and Development Division of the United Nations defines Social inclusion as the process by which people resident in a given territory, regardless of their background, can achieve their full potential in life. This, of course, includes the economic life of individuals, without neglecting other social and political aspects. Social cohesion is a related concept that can be defined as a feature of a society in which all groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition and legitimacy. This requires, among other things, avoiding the emergence of “parallel communities” that are divided (or even segregated) by language barriers within a given society.

Language policy can contribute to avoiding exclusion and segregation by promoting the linguistic integration of refugees and migrants, also in the labour market, and by fostering foreign language learning for mobile people who wish to spend a shorter or longer period of their lives abroad (e.g. international students). Language skills facilitate inclusion and cohesion because, among other things, they increase the capability of citizens and migrants to understand and communicate with the other members of society. It facilitates the access to (higher) education, which plays a key role in the development of an individual’s human capital.

Research questions

The number of potential research questions that are relevant for the conference is large. Here we present a non-exhaustive list that can help orienting prospective participants:

- Do language skills significantly contribute to the participation of individuals in the labour market?

- Which languages are more rewarded in the labour market and at which level of fluency? What differences among countries or regions can be observed in this respect?

- Do language skills improve international economic integration and trade?

- How does language competence affect the social inclusion of migrants and refugees? Which sociolinguistic barriers can hinder inclusion?

- Are language skills an important variable in employers’ recruiting decisions?

- Do some economic sectors make a more intensive use of language skills than other?

- What is the role of language policy in facilitating social inclusion and social cohesion?

- How do language education policies affect individuals’ migration decisions? Do foreign language skills significantly facilitate international labour mobility and therefore the economic integration of the European and the global labour market as a whole?

- What is the relationship between language skills in a lingua franca (e.g. English) and social integration in the host country where the lingua franca is not the locally dominant language? What differences can be found among low-skilled migrants and high-skilled (or “expats”) in this respect?

- Does a lingua franca increase social inclusion, or does it promote the emergence of separate networks of communication? What are the sociological implications of this?

Keynote speakers

The interdisciplinary nature of the conference is reflected by the variety of academic background of the invited keynote speakers

1. Economics

- Antonio Di Paolo: “The economic and social consequences of language-in-education policies” (AQR-IREA, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain)

- François Vaillancourt : “ Language policies and labour market earnings : plausible impacts and evidence from Québec ” (Université de Montréal, Canada)

- Ingo Isphording: “Immigrant language skills and labor market success” (IZA – Institute of Labor Economics, Germany)

2. Sociolinguistics

- Gabriele Iannàccaro: “Social inclusion and sociolinguistics” (Stockholms Universitet, Sweden)

- Sonja Novak: “Multilingualism at work: the case of firms in Slovenia” (Institute for Ethnic Studies, Ljubljana, Slovenia)

3. Sociology

- Amado Alarcón: “Measuring Occupational Language Skills” (Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Spain)

Date and Venue

12-13 October 2017

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin,

Berlin, Germany

Fees and payment methods

The participation fee is €150 until 1 September and then €200. It includes four coffee breaks, two lunches and the social dinner on Thursday 12th October.

The participation fee for students of Humboldt-Universität is €50,-.

It is possible to pay either by bank transfer or by Paypal.

Submission and deadlines

The length of abstracts should not exceed 350 words. Abstracts must be submitted to the address “templito@hu-berlin.de” by 15 May 2017. The successful applicants will be notified by 30 June 2017.

Working languages

You can send abstracts in English, Esperanto, French, German, Italian, Spanish, or Swedish.

Local organisers

REAL – Research group on Economics and Language

Institut für Erziehungswissenschaft

Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftliche Fakultät

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Bengt-Arne Wickström

Jürgen Van Buer

Michele Gazzola

Torsten Templin

Wiwex GmbH

Scientific committee

Agresti, Giovanni (Università di Teramo, Italy)

Chiswick, Barry (George Washington University, USA)

De Schutter, Helder (University of Leuven, Netherlands)

Dunbar, Rob (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom)

Dustmann, Christian (University College London, United Kingdom)

Gazzola, Michele (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany)

Ginsburgh, Victor (ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium)

Grenier, Gilles (Université d’Ottawa, Canada)

Marácz, Laszlo (Universiteit van Amsterdam, Netherlands)

Medda-Windischer, Roberta (European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano, Italy)

Shorten, Andrew (University of Limerick, Ireland)

Templin, Torsten (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany)

Van Buer, Jürgen (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany)

Von Busekist, Astrid (Sciences-Po, Paris, France)

Wickström, Bengt-Arne (Andrássy University Budapest, Hungary)

Wolf, Nikolaus (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany)

With the kind support of

- Institute for Ethnic Studies, Ljubljana, Slovenia

- ILT project (CSO2015-64247-P) – Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness

- The MIME Project (www.mime-project.org)

Call for papers on Russia’s global language promotion

Call for papers

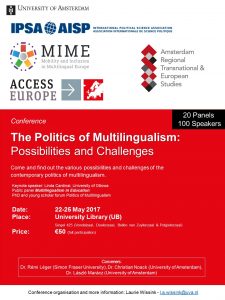

In collaboration with the International Political Science Organisation, ACCESS Europe, the Amsterdam School for Regional, Transnational and European Studies and the Migration and Inclusion in a Multilingual Europe (MIME) research group, the NEMESIS Jean Monnet Network is organising two panels at the conference “The Politics of Multilingualism” at the University of Amsterdam, 22-24 May 2017.

Both panels deal with

“Russia’s global language promotion: Between robust reassertion and soft securitisation”.

In the context of Russia’s current attempts at the economic and political re-integration of the post-Soviet space, geopolitical discourses stipulating Russia’s civilizational distinctiveness from the West play an important role. Russian culture and language, plus the latter’s historic role as a lingua franca in the region, are important arguments in such discourses. Since the mid-2000s, the Russian state channelled significant financial investment into the spread of Russian through language training and the dissemination of teaching materials.

Offering language courses and showcasing Russian culture is a legitimate cause, yet none of the new Russian organisations makes a secret of targeting their audience specifically in the ‘near abroad’ (the Russian term for the former Soviet republics) in the first place. In this area, the ascription of being a ‘Russian speaker’ has recently been instrumentalised to sustain Russian securitisation claims.

Outside the former Soviet space, Russian cultural institutions involved in the consolidation and

spread of the Russian language may in fact combine some of the functions of the former Soviet

‘friendship societies’ in cultural diplomacy. Against the backdrop of concerted Russian disinformation campaigns, the dissemination and sufficiently broad perception of Russian language media in countries of the former Soviet space or beyond (Germany, Israel) has more recently caused

considerable apprehension as well.

We invite papers examining the following questions:

Panel 1: The Russian Language as an Instrument in Russia’s Soft Power Toolbox”

– The role of Russian language in the definition of cultural or political affiliation with Russia, be it in the context of the “law on the compatriots”, in Russian Orthodox parishes abroad or among diaspora and migrant organisations.

– Programmes aiming at the consolidation or spread of Russian language use abroad, like the federal target program “Russian language” for 2016-2020;

– The institutional set-up of Russia’s support of Russian language use and education abroad, in

particular the activities of institutions like Rossotrudnichestvo or foundations like Russkii mir

in Russia’s “near abroad” and further afield.

Panel 2: Russia as a lingua franca and the use of Russian language media

– The legal status and the use of Russian among Russian speaking communities outside the Russian Federation, both within the “near abroad” and further afield (EU member states, Israel);

– Production, dissemination and monitoring of Russian language media (produced in Russia and abroad);

– The role of Russian language media in the mediascapes of countries with significant Russian speaking populations.

Deadline: Please send an abstract of up to 500 words and a short bio (max. 100 words) to

c.u.noack@uva.nl before 15 February 2017. Notification of acceptance will be issued at the end of

February 2017. Final workshop papers are due on 30 April 2017. As we are planning a publication of

the papers in a conference volume, all contributions should be original and not published elsewhere.

A conference fee of €50 covering lunches and a conference dinner applies for all participants at the conference “The Politics of Multilingualism”. Limited funding is available to cover accommodation and travel costs. Please indicate when submitting the abstract if you would like to apply for funding.

Conference organisers: Laszlo Márácz, Christian Noack (University of Amsterdam)

Call for Papers: The Politics of Multilingualism: Possibilities and Challenges

On 22-24 May 2017, the Amsterdam School for Transnational, Regional and European Studies of the Faculty of Humanities of the Universiteit van Amsterdam will host an international conference organized by ARTES (artes.uva.nl), ISPA’s RC50 (rc50.ipsa.org) and MIME (mime-project.org).

In recent years, global trends in migration, trade and overall mobility have continued to transform our objective realities and subjective experiences of linguistic diversity. More broadly, in many countries, the politics of multilingualism have raised new possibilities for collaboration and action as well as challenges to social solidarity and democratic life. In response, scholars in the broad field of language policy and planning have studied language policy choices, linguistic vitality and language revitalization, curriculum development and pedagogies, governing mechanisms and policy instruments, and explored the conditions for linguistic justice in complex societies.

This conference will provide an opportunity to examine and better understand these various possibilities and challenges associated with the contemporary politics of multilingualism. Proposals for individual papers or for panels are invited. We welcome case studies and comparisons, as well as papers adopting a theoretical or normative perspective. Established academics and early-career scholars are invited to submit proposals.

Our keynote speaker will be Dr. Linda Cardinal (University of Ottawa, Canada). Dr. Cardinal is Professor in the School of Political Studies and holder of the Chaire de recherche sur la francophonie canadienne et les politiques publiques at the University of Ottawa. She is one of Canada’s leading experts on language and politics, and her recent comparative work has focused on language regimes and state traditions. Dr. Cardinal is past president of IPSA’s RC50.

Proposals for papers should include full contact details (email address, mailing address, and affiliation) of the author(s) and an abstract of up to 250 words.

Panel proposals must include:

- A minimum of three papers and a maximum of four;

- Panel title and individual paper titles

- Short description of panel (up to 250 words)

- Contact details of chair, paper-givers and discussant

The final deadline for electronic submission of proposals is 20 January 2017. Notices of acceptance will be sent out no later than 15 February 2017. Proposals should be submitted to: l.k.maracz@uva.nl.

Conference registration will cost 50€ for all participants (paper-givers, discussants, chairs and attendees). Looking forward to seeing you in Amsterdam.

The organizers,

Dr. Rémi LÉGER (Simon Fraser University, rleger@sfu.ca)

Dr. László MARÁCZ (University of Amsterdam, l.k.maracz@uva.nl)

Dr. Christian NOACK (University of Amsterdam, c.a.noack@uva.nl)

Slides of the Expert Meeting on Multilingualism in Education are available

The slides of the talks presented in the expert meeting in March, 15, are now available here:

Meertaligheid in het Onderwijs: elke taal telt mee

Hogeschool Windesheim heeft het initiatief gelanceerd tot een landelijk Platform Meertaligheid in het Onderwijs. Het platform beoogt samen met andere hogescholen, met universiteiten en overige partners invulling te geven aan het gemeenschappelijke doel: elke thuistaal een plek te geven in het onderwijs.

Contactadres: cj.helsloot@windesheim.nl

Mondialisering bepaalt onze samenleving. We gaan grenzen over voor vakantie, werk of familie. Onze leefwereld is steeds diverser, en óók steeds meertaliger. Terecht dus dat er aandacht is voor vreemde talen in het basisonderwijs. Platform Onderwijs 2032 adviseert om vanaf groep 1 met Engels te starten, en staatssecretaris Sander Dekker roept op om Duits en Frans vroeg aan te bieden in grensstreekscholen.

Maar waarom alleen deze talen? Een derde tot de helft van de leerlingenpopulatie gebruikt thuis een andere taal, al dan niet naast het Nederlands. Zo zijn er kinderen met Surinaamse, Antilliaanse, Indonesische of Molukse wortels, en kinderen van arbeidsmigranten uit bijvoorbeeld Turkije, Marokko en meer recent, Polen of Roemenië. Er zijn kinderen van asielzoekers uit Iran, Afghanistan en Somalië, en nieuwe stromen vluchtelingen komen er aan, uit o.a. Syrië en Irak. En natuurlijk zijn er ook Nederlandse kinderen die thuis Fries of een dialect spreken. Voor al deze kinderen is meertaligheid een fact of life.

Deze vorm van meertaligheid krijgt echter in het onderwijs maar weinig ruimte en waardering. De rol van het Nederlands als voertaal staat buiten kijf, net als de focus op het versterken van de taalvaardigheid Nederlands. Bij het verwerven van het Nederlands, van het Engels of van welke taal dan ook, maakt de leerling met een ‘tweede’ taal indirect gebruik van zijn kennis. Zo doet de mens dat met alles: voortbouwen op wat je weet. Waarom mag dat niet expliciet worden benoemd als het om taal gaat?

Lang dacht men dat het kinderbrein niet meer dan één of twee talen aankon, dat het vroeg aanleren van het Engels ten koste ging van het Nederlands, en dat het gebruik van een andere thuistaal inburgering in de Nederlandse samenleving in de weg stond. Recent onderzoek laat zien dat kinderen met gemak verschillende talen naast elkaar kunnen leren en gebruiken, dat het beheersen van meer dan één taal culturele en economische verrijking betekent, én dat het cognitieve voordelen heeft. En misschien wel het belangrijkste inzicht: ruimte geven aan de eigen taal zorgt voor emotioneel evenwicht en voor een positieve houding van de leerling zelf. Wanneer eigenheid wordt toegestaan, nemen veiligheid en welbevinden toe.

Wat betekent het nu voor een leerkracht als er vier, tien of meer verschillende taalachtergronden aanwezig zijn in een klas? Hoe doe je dat, als je zelf geen Twents, Pools of Arabisch spreekt? Universiteiten, hogescholen en andere instellingen doen al jaren onderzoek naar taal en taalverwerving. Zij kunnen bijdragen aan bijscholing, begeleiding en lesmaterialen, voor alle leeftijden en sectoren. Dus, taalexperts, sla de handen ineen om leraren over de drempel te helpen. Bestuurders van universiteiten en hogescholen, geef toekomstige leerkrachten de handvatten om te werken in cultureel diverse omgevingen: een leerlijn meertaligheid in de pabo, een masteropleiding taalvergelijking en meertaligheid.

Laat elk mens zich ontwikkelen door ook zijn moedertaal, zijn thuistaal, daarbij in te mogen zetten. Een vreemde taal mag in de klas, de eigen taal helpt in de klas, de thuistaal telt in de klas!

Zwolle, 25 november 2015

Dr. Karijn Helsloot & Dr. Gerrit Jan Kootstra, Hogeschool Windesheim

Harry Frantzen, Hogeschool Windesheim Dick de Wolff, Hogeschool Utrecht

Pieter Muysken, Radboud Universiteit Guus Extra, Tilburg University

Hans Bennis, Meertens Instituut

Jacomine Nortier, Universiteit Utrecht

Rick de Graaff, Universiteit Utrecht / Hogeschool Inholland Ellen-Rose Kambel / Rutu Foundation

Ad Backus, Tilburg University

Alex Riemersma, Stenden Hogeschool, NHL Hogeschool Leeuwarden Alessandra Corda, Hogeschool van Amsterdam

Leendert-Jan Veldhuijzen, De Nieuwe Internationale School Esprit Mathi Vijgen, Hogeschool Utrecht

Hanke Drop, Hogeschool Utrecht

Leonie Cornips, Maastricht University, Meertens Instituut

Merel Keijzer, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Jan Berenst, NHL Hogeschool Leeuwarden

Paul Leseman, Universiteit Utrecht

Joep Bakker, Radboud Universiteit

Abram de Swaan

Liesbeth Schlichting

Folkert Kuiken, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Erna van Koeven, Hogeschool Windesheim

Maaike Hajer, Hogeschool Utrecht

Anne Baker, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Jeannette Schaeffer, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Jan Doelman, Hogeschool Windesheim

Martin ’t Hart, Hogeschool Inholland

Hanneke Pot, Hogeschool Inholland

Irene van Adrighem, Hogeschool Inholland

Anneke Smits, Hogeschool Windesheim

Frederike Groothoff, leerkracht PO en UU

Sharon Unsworth, Radboud Universiteit

Aafke Hulk, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Eddie Denessen, Radboud Universiteit

Wander Lowie, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Beppie van den Bogaerde, Universiteit van Amsterdam / Hogeschool Utrecht Everdiene Geerling, Stichting Nederlands Onderwijs in het Buitenland

Orhan Agirdag, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Janet van Hell, Pennsylvania State University, USA

Ton Dijkstra, Radboud Universiteit

Bert Meijer, Hogeschool Windesheim

Lex Stomp, Hogeschool Windesheim

Federico Gobbo, Universiteit van Amsterdam / Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca / Università degli Studi di Torino

László Marácz, Gumilyov Eurasian National University / Universiteit van Amsterdam